Our feature series the ‘Device That Made Me’ is where we speak to famous creatives about the one piece of tech that transformed their lives for the better. For part two, award-winning photojournalist Stephen Shames speaks with Christine Ochefu on how the Leica M4 camera helped him document the trials and tribulations of the US Civil Rights Movement.

Despite being nearly 60 years old, the Leica M4 camera remains popular today, with this small but sturdy brass gadget commanding hefty prices on the second-hand market. From an iconic portrait of political revolutionary Che Guevara, which would be hung on the walls of millions of students, to the Pulitzer Prize-winning ‘Napalm Girl, the Leica brand of cameras are synonymous with capturing historical, paradigm-shifting moments.

Anyone who’s ever taken a photo will also understand the struggle of capturing subjects at their most natural. Refreshingly, the Leica M4 allows for an intimate closeness to your subject, which is due to its no-frills, unassuming appearance; essentially helping instantly relax the person on the other side of the lens. Maybe then that’s why the legendary American photographer Stephen Shames would find this particular device his best companion to create a lifetime of such enduring images.

This critically acclaimed 78-year old photo essayist has spent decades snapping bold imagery that isn’t afraid to speak truth to dictatorial power, subsequently documenting enormous social change and political friction in the US. From a humble beginning as a staffer at University of Berkeley’s influential Berkley Barb Newspaper in the late 60’s, he sparked up an enviable photography career, which has helped us to better understand the human beings at the core of the American Civil Rights Movement.

The Black Panther Party in 1969. Photo by Stephen Shames.

Shames would document the War on Vietnam; the speeches of Martin Luther King; poverty across America; and the assault on - and fight for - black civil liberties that occurred across the USA in the 1960s and 70s. The veteran photographer notably spent time shadowing the radical Black Panthers, his work with this grassroots political group a great example of actualizing the ‘Rainbow Coalition,’ a political idea that solidarity and community could exist across racial and class lines. The photographer became a trusted window into the Panthers’ inner workings and, more importantly, a vehicle for depicting an honest, tender portrayal of the loving community they created behind the bold By Any Means Necessary mantra.

“My pictures have a lot of very intimate shots, and I'm in a lot of places that aren't tourist places" - Stephen Shames, photographer

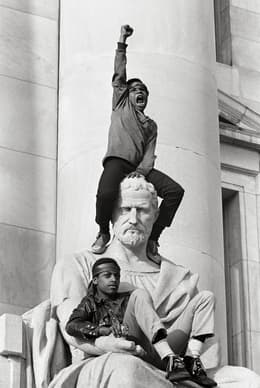

This was achieved through romantic portraits Shames created of smiling Black Panther’ kids taking school classes in berets; Huey Newton joyously holding up a Bob Dylan LP; and Angela Davis smoking a cigarette after being released from the chaos of prison. “Sometimes the picture becomes more than what it is,” Shames says, the native New-Yorker speaking to us from his home in the city. “It's not just the documentation of some kids sitting on a statue; people see it as a documentation of the black liberation struggle. That's the power of photography; sometimes a picture can be an emotional representation. And that's what art is, isn't it? If it's great art, it's always more than just what it appears at face value.”

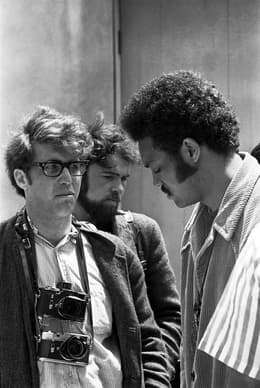

Stephen Shames, his Leica M4, and civil rights activist Jesse Jackson. Photo supplied by Stephen Shames.

All these years later and the Leica M4 remains a trusty tool in Shames’ arsenal. And although there are more advanced cameras on the market, photography enthusiasts like Shames insist the Leica M4 version remains “exactly right” for purpose; a compact, unassuming device, with a sturdy design built to last. He says it’s the perfect device for showcasing raw truth.

“My pictures have a lot of very intimate shots, and I'm in a lot of places that aren't tourist places,” the photographer - who at one point could of been snapping a 60’s Vietnam march in the pouring rain one day, or moving through dusty refugee camps in Uganda the next - explains. “People would say, ‘oh yeah, I got a camera like that.’ Because the Leica M4 doesn't look like a fancy professional camera, it’s more of an ice breaker.”

He continues: “When you had a professional camera, people didn't want you to take pictures as they thought you were part of the untrustable news media. The Leica M4 allowed me to become more invisible.” We spoke to Shames about years capturing America’s thorny sociopolitical history, using his Leica M4 like a creative partner, and why this near-indestructible device has lasted the test of time. The following conversation has been lightly edited for clarity.

Two children climb a statue during a protest in New Haven amid the 1970 trial of Bobby Seale. Photo by Stephen Shames.

When did you start using your Leica, and what made you pick it up in the first place?

Stephen Shames: When I started working at the Barb newspaper, I met [fellow photojournalist and photographer] Alan Copeland, who became my best buddy and mentor. He was a much more accomplished photographer at the time. He introduced me to the German high-end camera brand Leicas and convinced me to get rid of this cheap little pawn-shop camera that I had previously.

The first one I got may have been an M3, but soon after I got an M4; I loved that camera. The lenses were incredible, really, really sharp. You could focus in low light because you were looking through the rangefinder. People didn't think it was a big, fancy camera, so it was great for street photography and walking around unobtrusively.

I've heard some photographers talk about cameras like creative partners, or even like they have individual personalities. Is that how you felt with your Leica at times?

Stephen Shames: I felt like the cameras were part of me, yes. I always had it in my possession. In the same way you'd never walk out of the house naked without clothes, if I didn't have this camera, well, I felt completely naked. It was almost like something you put under your pillow at night. It was like a partner: part of me, or an extension of my eye.

Poverty in America: a child sleeps in a car. From 1985 in Ventura, California. Photo by Stephen Shames.

One thing I noticed about your work is that it's very empathetic, and doesn't feel voyeuristic, despite you often photographing controversial subjects in delicate situations. How do you keep empathy in your work, especially when you're photographing communities you're not necessarily from yourself?

Stephen Shames: I worked with this great political journalist Errol Caldwell, who was a staff journalist for The New York Times. He used to say to me: ‘Steve, you have to share their pain.’ When I photographed the homeless families, like that kid and his family who were living on the beach in a state park, I bought a tent and camped out with them. When I was doing the Outside the Dream: Child Poverty in America series, if I was photographing, say, an unemployed steelworker family in Indiana, I literally slept on their sofa, ate meals with them, and got to know them, too. That's the only way you can truly learn about people's lives; you're sharing their experience. Conversely, you need to share the joy too. That's what true empathy is; getting inside someone else's emotion, good or bad.

A Black Panther education programme for working class children. Photo by Stephen Shames.

Though you primarily shoot digital now, I've noticed that there is a resurgence in classic film cameras among younger generations. Why do you think people keep returning to that kind of art form even though digital is so widely available?

Stephen Shames: Nothing ever completely disappears. There's a quality to film that's really different; I don't know that digital will ever produce color images as great as Kodachrome, for example, or black and white images as wonderful as [Kodak] TRI-X. Back when cameras were all mechanical, they lasted forever. Now, with digital cameras, every two or three years they're almost obsolete; they come out with new ones, and you're always updating the software.

I saw a funny thing someone posted on Facebook; it said that back in the old days before appliances were ‘smart,’ they just lasted forever. Now, our smart appliances are made so you have to get a new one every two or three years, whether it's a stove, refrigerator, dishwasher, or phone! But you could buy a Leica from the 1940s, 50s, or 60s, they still work in 2025. My Leica M4, I have had it for well over 30 years. Once in a while you had to take it to the repair place and get them to clean it, sure, but it lasted forever – you would have had to drop it from a second-floor window onto a cement sidewalk to mess it up.

Martin Luther King speaking at an anti-war rally at UC Berkeley in 1967. Photo by Stephen Shames

Your photography often captures difficult imagery and can produce quite an emotional response when looking at it. Even in the midst of challenging subject material, has photography ever been therapeutic for you?

Stephen Shames: Absolutely. My mom was a poet, and I grew up in an artistic household. So I was exposed to art, and kind of considered myself an artist, but I could never draw or paint or do anything with that. So the camera and photography was really my art form.The difference between most people and artists is artists use our screw-ups and imperfections to learn and create great art. As artists, we know we're fucked up, [but] we use that tension to create art and that's the healing process of it. It heals us, and hopefully seeing great art also heals other people.

What is healing? Number one is identifying that you're upset and what it is that upsets you. Secondly, analyzing it. In photography, you go through all those thoughts through other people's lives, and it helps you deal with what's happened in your life by creating their picture. A lot of us are drawn to people on the edges of society, people going through tough times. I photograph child labor or a child soldier that isn't my experience, or a steelworker who lost his job and the family is going through a crisis. Emotionally, that can feel like my experience of things that happened to me and my family, even though they are different. All of us have crises in our lives, and taking pictures is a process of understanding.

An original illustration by Hayley Wells. Stephen Shames: A Lifetime In Photography is out now.